Musicians speak to the power of Frank Zappa’s music — an unscientific IndieEthos survey

July 30, 2016

In the documentary Eat That Question: Frank Zappa in His Own Words, the film’s subject sometimes comes across as a bit frustrated by his cult of personality. One thing he bemoans more than once is that most people know his name but few buy his music. The film itself is also more focused on his interviews than his performances. It didn’t even take day after I published my review (Eat That Question: Frank Zappa in His Own Words highlights the mind behind the music … and the ideology — a film review) before a friend texted me to ask “Who is Frank Zappa?”

Jon Anderson of Yes gets chatty about carrying on; full interview in ‘Miami New Times’

November 8, 2013

Jon Anderson is one of those early pioneers of the British progressive rock scene still working who has earned the title of living legend. He was part of many important albums of the prog scene as a co-founding member and frontman of Yes. What a breath of fresh air that he appeared game to entertain some questions that I’m sure he has heard often with warmth and some amusement.

Jon Anderson is one of those early pioneers of the British progressive rock scene still working who has earned the title of living legend. He was part of many important albums of the prog scene as a co-founding member and frontman of Yes. What a breath of fresh air that he appeared game to entertain some questions that I’m sure he has heard often with warmth and some amusement.

For instance, what happened that made the band carry on without him? “I was going to get back together with the band [in 2008],” he admitted while chatting over the phone, during some grocery shopping, “and then I got really sick, and then that’s when the band decided to move on and carry on touring with another singer and I just thought, well, I gotta get better first. It took me a while. It took me about eight months, nine months. And then I said, OK, well, they’re out there doing their thing maybe I should go out and do my thing, and that’s when I started really touring as a solo artist more and more, and it has become part of my life.”

It’s probably an explanation his given many times before. The fact that he put up with such questions twice in a row after my recorder failed following a 20-minute chat stands as proof that he is far from allowing an ego to overtake his humanity.  I regret that I lost a nice exchange about the band’s 1973 ambitions double-album Tales From Topographic Oceans, where he not only offered insight into its themes inspired by the Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda but also what exploring that philosophy meant to him personally. He said, back then, record labels and some bands, were all about maximizing profit and excess. He was more interested in keeping his ego in check and maintaining a perspective unsullied by money and fame. Exploring this Eastern philosophy has helped keep him grounded as well as inspired much of Yes’ fantastic music and lyrics. We also spoke about meditation, which he still practices, and how Yes’ albums capture the sensation of meditation and bliss in its music.

I regret that I lost a nice exchange about the band’s 1973 ambitions double-album Tales From Topographic Oceans, where he not only offered insight into its themes inspired by the Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda but also what exploring that philosophy meant to him personally. He said, back then, record labels and some bands, were all about maximizing profit and excess. He was more interested in keeping his ego in check and maintaining a perspective unsullied by money and fame. Exploring this Eastern philosophy has helped keep him grounded as well as inspired much of Yes’ fantastic music and lyrics. We also spoke about meditation, which he still practices, and how Yes’ albums capture the sensation of meditation and bliss in its music.

Even though he is no longer with Yes, Anderson continues to compose and record new material as a solo artist not all that different from Yes. In 2011, he self-released a 20-minute-plus digital-only single entitled “Open” (Support the Independent Ethos, purchase direct through Amazon via this link). Not long after, he teased a follow-up called “Ever” that has yet to see release. “Yeah, I started it last year,” he noted, “and it has taken longer than I expected it. We’re down to the last framework of the songs—two-and-half songs. Altogether, it’s about eight songs that are all inter-working together. It’s still not quite finished. I’m working with them now with a friend … It’s a slow process. Music never happens when you think it is going to happen. You work on something and a week later you say, ‘Nah, that really didn’t work. I gotta try again.’ And you do. You gotta keep going until it feels right.”

Let’s face it, any fan of Yes’ music is waiting to hear about his return to fronting the band that has comfortably gone on without him. Well, he did answer that question as well as reveal plans with former Yes keyboardist Rick Wakeman in our interview, the bulk of which can be read in the “Miami New Times” music blog “Crossfade.” Jump through the blog’s logo below to read that article:

As the quote in the headline notes, Anderson may indeed once again front Yes. In an earlier interview I did with Yes drummer Alan White, for the “Broward-Palm Beach New Times” music blog “County Grind,” his former bandmate hinted at the same possibility. You can read that interview by jumping through the blog’s logo below:

Jon Anderson takes the stage Sunday, November 10, at the Colony Theater in Miami Beach. Two shows: 6 p.m. and 9:30 p.m. Tickets cost $81.95. All ages. Call 800-653-8000 or visit ticketmaster.com. For more Jon Anderson tour dates, visit his official website.

Alan White of ‘Yes’ talks ‘Cruise to the Edge’ and early Yes; my profile in “New Times”

March 21, 2013

While giant music festivals continue to bring in huge crowds to cities like Chicago (Lollapalooza) and even right here in my hometown of Miami (Ultra), more niche acts with dwindling followers who are growing more affluent are taking to the high seas (see my Weezer Cruise coverage). One of the more recent groups of musicians trying out the cruise music festival circuit are a batch of progressive rock bands who both started the genre and followed in their footsteps. The Cruise to the Edge tour sails from Fort Lauderdale, Florida next week, headlined by Yes, the band who produced one of the great early ‘70s prog albums: Close to the Edge.

While giant music festivals continue to bring in huge crowds to cities like Chicago (Lollapalooza) and even right here in my hometown of Miami (Ultra), more niche acts with dwindling followers who are growing more affluent are taking to the high seas (see my Weezer Cruise coverage). One of the more recent groups of musicians trying out the cruise music festival circuit are a batch of progressive rock bands who both started the genre and followed in their footsteps. The Cruise to the Edge tour sails from Fort Lauderdale, Florida next week, headlined by Yes, the band who produced one of the great early ‘70s prog albums: Close to the Edge.

While my more youthful colleagues at “New Times” covered the hanging asses and same-old beats at Ultra, I had an opportunity to speak to two prog legends who will be on this cruise: Yes drummer Alan White and U.K. bandleader Eddie Jobson. Both have landlocked shows, which I wrote about in the two “New Times” publications that cover South Florida.

The first musician I spoke with was White. My article was limited to the “County Grind” blog at the “Broward-Palm Beach New Times.” You can read it by jumping through the logo for the blog below:

We covered a lot of territory on the phone. Including his memory of stepping into Bill Bruford’s shoes, when he left Yes for King Crimson in 1972. He remembers having to learn the early albums quickly. Close to the Edge was the last album Bruford recorded with the band. White came to Yes at just 23 years of age with some high-profile studio experiences with John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band and George Harrison. “I had three days to learn the repertoire including the new album they had just recorded,” White told me via phone, from a tour stop in Aspen, Colorado, “so I had to learn a lot of stuff in a few days.”

Up to that point, this was some of the most complex music White had to learn, as Bruford had made a name for himself in prog as one of the genre’s most complex rhythm men. “Bill’s obviously a different drummer than me in certain ways, in certain ways not,” White noted. “I can do the technical stuff, but I can also do the rock ‘n’ roll background. I had my own band that was a rock/jazz type of thing for a long time before I joined Yes, so I was kinda prepared for all the time signatures, and that kind of stuff, which I got into and picked up on, and changed them a bit, to a degree, but kept most of the parts that made the music what it is.”

“Bill’s obviously a different drummer than me in certain ways, in certain ways not,” White noted. “I can do the technical stuff, but I can also do the rock ‘n’ roll background. I had my own band that was a rock/jazz type of thing for a long time before I joined Yes, so I was kinda prepared for all the time signatures, and that kind of stuff, which I got into and picked up on, and changed them a bit, to a degree, but kept most of the parts that made the music what it is.”

To read more of my conversation with White, jump through the link above. I plan to attend Yes’ live show and review it for the “New Times.” White said the band plans to play three of Yes’ more important albums from the ‘70s live: the Yes Album (1972),  Close to the Edge (1973) and Going for the One (1977). The show will take place at the same venue where I caught the Genesis tribute band the Musical Box, as it re-created that band’s acclaimed 1974 prog masterpiece the Lamb Lies Down on Broadway live (Genesis tribute band The Musical Box’ take on ‘The Lamb,’ and this writer returns to “New Times”). I shall up-date this post with a link to that review when it is published, so, Yes fans, take note and bookmark.

Close to the Edge (1973) and Going for the One (1977). The show will take place at the same venue where I caught the Genesis tribute band the Musical Box, as it re-created that band’s acclaimed 1974 prog masterpiece the Lamb Lies Down on Broadway live (Genesis tribute band The Musical Box’ take on ‘The Lamb,’ and this writer returns to “New Times”). I shall up-date this post with a link to that review when it is published, so, Yes fans, take note and bookmark.

Meanwhile, my interview with Jobson in “Miami New Times” music blog “Crossfade” will also appear shortly, I’ll link here when that post appears. We spoke more in depth about the formation of U.K. and what he considers the last of the ‘70s prog rock groups and the place of prog in the ever-shifting landscape of popular music. He was quite insightful.

Update: Jump to the Jobson interview here (it has a link within it to more of our conversation and lots of vintage images and videos):

Eddie Jobson of U.K. on popular music: “Everything’s been superficialized;” my interview in “New Times” and more

Update 2: Jump through the image below of the band performing at the Hard Rock Live on Sunday night for the live review:

I first heard Pink Floyd’s 1979 double album the Wall sometime in 1984, as a 12-year-old boy. A neighbor at my apartment building loaned me a cassette version, and I played it through only once, before going to bed. That night, after climbing under the sheets in the bottom bunk of the bed I shared with my little brother, I suffered a nightmare. I no longer remember what I dreamt, but I knew I had experienced the Wall’s honest, primal power even though I could barely understand what was going on in the “narrative” of this concept album. I would not go back to listen to it again until about five years later.

In the years since, I have covered Pink Floyd reissues and books as a freelance music writer, often in the pages of the record collector’s magazine, “Goldmine.” I personally enjoyed owning the Shine On CD box set in 1992, which included the full Wall album, after saving up some money as a poor college student. A friend who worked at a record store would help me out with his employee discount.  I have seen Alan Parker’s film version of the album, conceived with the Wall’s principal songwriter, Roger Waters on VHS. I own the first edition DVD version and have watched it several times since, even with commentary. I also reviewed Water’s staging of the album in Berlin when a DVD of the show came out in 2003, for “Goldmine.” I have grown to know the album well, and though it no longer frightens me, its punch remains and probably always will.

I have seen Alan Parker’s film version of the album, conceived with the Wall’s principal songwriter, Roger Waters on VHS. I own the first edition DVD version and have watched it several times since, even with commentary. I also reviewed Water’s staging of the album in Berlin when a DVD of the show came out in 2003, for “Goldmine.” I have grown to know the album well, and though it no longer frightens me, its punch remains and probably always will.

Though the album is known for furthering the rift between Waters and his collaborators in Pink Floyd, I have always found an almost auterist benefit to Waters handling the majority of the songwriting for the Wall. The album seems to chronicle the mental breakdown of a rock ‘n’ roll star who tangles with his sense of self in the wake of his fame. Sex (“Young Lust”) and drugs (“Comfortably Numb”) were never depicted more bleakly on a rock ‘n’ roll record. It was honest and genuine, and Waters dives deep, going back to growing up fatherless thanks to World War II (“Goodbye Blue Sky”). He examines the role of a smothering mother (“Mother” and “The Trial”) and domineering boarding school education (“Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2”). The references to a wall throughout the album provide a metaphor about the gradual psychological isolation of the protagonist to the outside world. The only cure? “Tear down the Wall,” chants a mob at the end of the next-to-last track of the album. Chronicling a dynamic, if gloomy journey into isolation, the album produced some of the band’s greatest hits like the aforementioned “Comfortably Numb” and “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2.” The music is grim and potent throughout, until a wonderful, if subtle shift in tone at album’s end. “Outside the Wall” is an underrated number that illuminates and subverts all the tracks that unfolded before it. It truly sounds like hope (though “it’s not easy”). All the self-important, if self-critical posing, both ironic and bombastic, is over. There is no more spectacle to be seen here. There’s a mellowness in Waters’ voice joined by a harmonious chorus of other voices. The rock elements are gone, as the main instrument is clarinet, augmented by the high-pitched hum of a droning accordion and sprightly strum of a mandolin. It makes for an ingenious tonal shift that offers an often-overlooked turnaround, not to mention a bright sense of hope to the mostly gloomy album.

The references to a wall throughout the album provide a metaphor about the gradual psychological isolation of the protagonist to the outside world. The only cure? “Tear down the Wall,” chants a mob at the end of the next-to-last track of the album. Chronicling a dynamic, if gloomy journey into isolation, the album produced some of the band’s greatest hits like the aforementioned “Comfortably Numb” and “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2.” The music is grim and potent throughout, until a wonderful, if subtle shift in tone at album’s end. “Outside the Wall” is an underrated number that illuminates and subverts all the tracks that unfolded before it. It truly sounds like hope (though “it’s not easy”). All the self-important, if self-critical posing, both ironic and bombastic, is over. There is no more spectacle to be seen here. There’s a mellowness in Waters’ voice joined by a harmonious chorus of other voices. The rock elements are gone, as the main instrument is clarinet, augmented by the high-pitched hum of a droning accordion and sprightly strum of a mandolin. It makes for an ingenious tonal shift that offers an often-overlooked turnaround, not to mention a bright sense of hope to the mostly gloomy album.

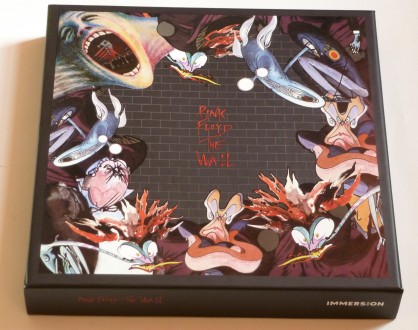

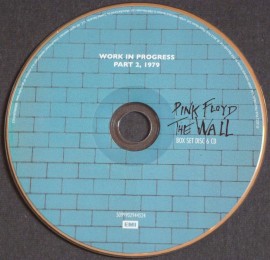

The Wall Immersion set contents

(clicking on images below will give you a hi-res view)

The Wall is a true masterpiece of rock concept albums. It is the sole, intensive “Immersion” box set of the recent Pink Floyd reissues by EMI I was interested in owning because I was real curious about what else went into making this album (all those demos!). EMI Records was generous enough to offer me a review copy for an intensive look at the extras packed inside the box that sells at a suggested retail price of just over $100. The price is justified by lots of physical elements, the most bizarre of which includes a velvet bag of three white marbles with the lined pattern of bricks familiar to anyone who has seen the album’s cover (a reference to “They must have taken all my marbles away”?).

The lines on the marbles arrived a bit broken up and worn, so whatever paint used was not the right quality for lasting handling (A tiny slip of paper inserted among them says “Glass Marbles Made in China”). They also are not perfectly round with some indentations on the surface. Also among the weirder items included in the box: a fringed gray scarf with the Wall pattern and the marching hammer logo printed at each edge.

It looks a bit cheap and marks a fashion trend that has passed on most hip men and was probably never in fashion for the hardcore Pink Floyd fan this set is designed for. Maybe someone’s wife would like it? There is also a set of cheap cardboard coasters that spell out the band’s name.

Beyond the coasters, the paper items are a bit more interesting. There are three black paper envelopes of varying sizes. The one marked “memorabilia” includes a replica backstage pass to a Wall show at the Nassau Coliseum, February 26, 1980. There is also a full-color, embossed ticket for a show in Berlin.

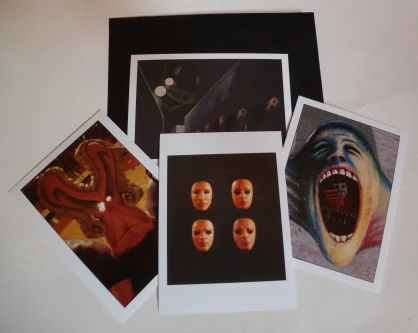

Another envelope is labeled “collector’s cards,” which contained four cards with pictures that are also in the books enclosed with this set. On the reverse side of the image there is text, and they are numbered various numbers out of 57. The text side has a song title and part of the lyrics oriented with the image on the reverse side.

The text side also refers to the cards as “anti-cigarette cards” because, apparently, cigarette packs back in the day of this album’s original release would come with such cards as added incentive for smokers. The view on smoking nowadays has changed much in the years since these cards first emerged. Now, these cards can apparently be found in various Pink Floyd products.

The third envelope is labeled “Mark Fisher Cards” and contains larger-formatted, one-sided cards of sketches depicting the stage design of the Wall show by Mark Fisher.

Other paper stuffs include an art print of an illustration of “the Wife” by Gerald Scarfe from the art he designed for both the inside of the album and the stage show (the creature below would later be created as a giant blow-up puppet with light-up neon lips and eyes).

There is also a folded up giant-sized poster with the lyrics of all the songs on the album, written out in the same ferocious script Scarfe used as the original lyric sheet of the album.

Finally there are two soft-covered booklets and a pamphlet with song titles for every disc enclosed and credits to the engineers, designers and musicians involved.

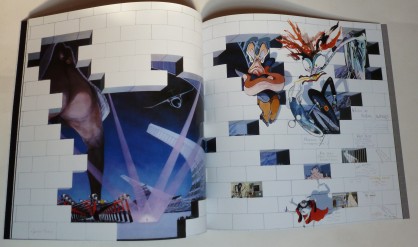

The larger of the books, simply titled “Pink Floyd The Wall,” contains photographs of the band during the Wall show, as well as the set pieces, behind-the-scenes images, sketches by Fisher and Scarfe and the lyrics as designed by Scarfe. The layout was conceived by Storm Thorgerson whose Hipgnosis studios had a longtime working relationship with Pink Floyd up until the Wall.

The other, slightly smaller, book titled “The Wall Pink Floyd Circa 1980-1 Booklet For The Immersion Box Set” contains nothing but photos of Pink Floyd during the Wall show circa— of course— 1980 and 1981. This one is edited by one of the photographers involved: Jill Furmanovsky. There are no essays or interviews at all in these books, however. Taking that into consideration, the books enclosed in the Wall Immersion set only deserve a fraction of attention that the thick, hardcover book I remember from the Shine On box set warranted*. There is nothing to really read or absorb beyond the lyrics and photos. The Wall Immersion booklet does have an interesting back cover image and brief essay showing the reach of the band into the war-torn country of Sarajevo in 1999:

I would have liked further essays with longer, more in-depth analysis of the album or its conception. Though the plethora of period pictures of the band performing the Wall in both the Immersion booklet and the Wall booklet are nice at capturing this particular moment of Floyd’s career, they beg for some context beyond the album’s lyrics and credits. The glossy paper is of fine quality and will certainly offer an upgrade to any other inserts in any other version of this album and lyrics from the album, but they deserved a little more attention by the design team.

The true substance of the box appears in the seven discs enclosed in— of all things— individual cardboard sleeves.  I am sure I speak for many collectors when I protest the use of cardboard sleeves without any protection to the discs, so allow me one more complaint. Japanese releases in cardboard sleeves always come in scratch-preventive plastic sleeves. OK, so there is one tray in this box, below all the ephemera, with cardboard hubs designed to hold four of the discs. Still, for the price tag of this set, plastic trays that prevent the play surfaces from any physical

I am sure I speak for many collectors when I protest the use of cardboard sleeves without any protection to the discs, so allow me one more complaint. Japanese releases in cardboard sleeves always come in scratch-preventive plastic sleeves. OK, so there is one tray in this box, below all the ephemera, with cardboard hubs designed to hold four of the discs. Still, for the price tag of this set, plastic trays that prevent the play surfaces from any physical  contact could have easily been used instead of all this cardboard, which can scratch play surfaces and attract moisture.

contact could have easily been used instead of all this cardboard, which can scratch play surfaces and attract moisture.

That said, I have long let go of any illusions that CDs or even LPs will last “forever” when treated with care, so I am not too bothered by the quality of the design. Still, I want to speak for some of the more serious collectors out there. But also, to address the serious collectors, I handle all of my CDs and records with as much care as possible, but I know I will be long dead before the elements seriously degrade them or I’m just plain over them and another reissue comes down the pike. I still have the beat up copy of the hardback book that came in the Shine On box set. The outer box grew so worn, I decided to throw it out and pack the CDs on my shelf, showing of the Darkside of the Moon cover art pattern that appears on the black CD jewel cases’ spines:

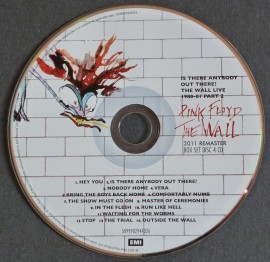

The Wall CDs

Finally, on to the music. Though the art on the labels have been redesigned for the box set, the audio on the two Wall CDs features the same remaster work by the band’s longtime engineer James Guthrie and Joel Plante, released last year as part of EMI’s 2011 remaster campaign of the entire Floyd catalog.  I have already reflected on the terrific remastering job of these albums, including the Wall (As Pink Floyd reissue mania continues, allow me a few words on said band), one of the major highlights being the clarity in the vocals. These new mixes allow the singers’ words to pop out without disturbing the original mix. I think purists have complained of nit-picky details, but seriously, nothing super-altered has emerged. This was not George Lucas going into the original Star Wars and adding whole scenes with digital cartoons or altering characters à la Han-shoots-first. This is a faithful polishing job that does fair justice to the source material.

I have already reflected on the terrific remastering job of these albums, including the Wall (As Pink Floyd reissue mania continues, allow me a few words on said band), one of the major highlights being the clarity in the vocals. These new mixes allow the singers’ words to pop out without disturbing the original mix. I think purists have complained of nit-picky details, but seriously, nothing super-altered has emerged. This was not George Lucas going into the original Star Wars and adding whole scenes with digital cartoons or altering characters à la Han-shoots-first. This is a faithful polishing job that does fair justice to the source material.

The live CDs

Besides the remastering of the classic album, Guthrie and Plante went to work resurrecting Is There Anybody Out There? a full-length concert performance of the Wall recorded over the course of the band’s brief Wall tour in 1980-81. Any true Pink Floyd fan would most likely already own the original version, released as both a 2-CD set and a deluxe edition with a hardback book, in 2000.

It’s a well-known live album compiled from various shows of the original tour but still following the order of songs on the Wall. The differences in the songs from the original album should prove of interest to any fan with a close knowledge of the Wall.

Is There Anybody Out There? opens with an announcer typical of many live shows in the day. He says, “…Before the show begins the house management would like to request just a few things. First, please no fireworks…” as the sound of the musicians warming up starts to drown out part of the speech (for a split second, it almost sounds as if the band is gearing up to play “One of Theses Days,” the opening track to Meddle).  Just as he finishes, “Well, I think the band’s ready to go now … no, no. Not quite yet. One thing I would like to point out, upon conclusion of the show…” the band pounds the man’s voice into oblivion with booming intro of “In the Flesh?”. It offers a great stage set-up to the fact that this is the performance of a concept album chronicling the psychic unraveling of a rock star poisoned by fame. In the years that have passed since 1981, this announcement sounds quaint, as security nowadays can do little to deter the pocket recorders not to mention smart phones most concertgoers bring to shows. More than ever, like it or not, the varying lights of smart phones and digital cameras seem part of a show. This amusing intro only heightens the classic feeling of this rock album that has well stood the test of time beyond the need of such announcements.

Just as he finishes, “Well, I think the band’s ready to go now … no, no. Not quite yet. One thing I would like to point out, upon conclusion of the show…” the band pounds the man’s voice into oblivion with booming intro of “In the Flesh?”. It offers a great stage set-up to the fact that this is the performance of a concept album chronicling the psychic unraveling of a rock star poisoned by fame. In the years that have passed since 1981, this announcement sounds quaint, as security nowadays can do little to deter the pocket recorders not to mention smart phones most concertgoers bring to shows. More than ever, like it or not, the varying lights of smart phones and digital cameras seem part of a show. This amusing intro only heightens the classic feeling of this rock album that has well stood the test of time beyond the need of such announcements.

The live album enforces the notion that Pink Floyd was more than just a creative studio band.  Their shows were amazing live experiences, even if they maintained a dedication to the original recordings, for the most part. Even though the band extends a few songs with meandering solos during Is There Anybody Out There?, the songs still cut close to the original recordings. “Mother” goes on for 7:55 thanks to some particularly passionate indulgence the original version does not have. The first CD ends with an instrumental overture called “The Last Few Bricks” featuring themes from many of the album. It worked as a musical interlude so stage hands might complete adding “the last few bricks” to the large, white wall, which covered the band for most of the second half of the show. Though this wall obscured the band for much of the show, it offers a poetic touch that reinforced the band members as faceless artists and not pop rock idols who needed spotlights shining on them. They were from a time and a genre that preferred anonymity and wanted only the music to matter.

Their shows were amazing live experiences, even if they maintained a dedication to the original recordings, for the most part. Even though the band extends a few songs with meandering solos during Is There Anybody Out There?, the songs still cut close to the original recordings. “Mother” goes on for 7:55 thanks to some particularly passionate indulgence the original version does not have. The first CD ends with an instrumental overture called “The Last Few Bricks” featuring themes from many of the album. It worked as a musical interlude so stage hands might complete adding “the last few bricks” to the large, white wall, which covered the band for most of the second half of the show. Though this wall obscured the band for much of the show, it offers a poetic touch that reinforced the band members as faceless artists and not pop rock idols who needed spotlights shining on them. They were from a time and a genre that preferred anonymity and wanted only the music to matter.

The DVD

The seventh disc is a DVD, which is coded for all regions, though in the NTSC format. It features lots of fantastic archival footage of the band’s live shows in the early eighties, culled together for a 50-minute documentary put together in 2000 by EMI called Behind the Wall.  It features interviews with the band members and narration that explains what was happening in and around the band at the time. There is also a nice detour into what happened before their pinnacle of fame, leading up to the live production of the Wall. Waters talks about his growing disdain for the sort of rock ‘n’ roll stadium audience whose participants just jumped on the bandwagon of popular trends or what was hot on the pop charts, following it to the venue. He says this is why he conceived the Wall. He truly wanted to separate the band from the audience and build a huge wall on stage that the band could play behind. He addresses a famous incident he seems a bit ashamed of in retrospect where he spit on a kid pushing his way toward the stage. “Afterwards I became really depressed and thought, ‘My God, what have I been reduced to?'” he says.

It features interviews with the band members and narration that explains what was happening in and around the band at the time. There is also a nice detour into what happened before their pinnacle of fame, leading up to the live production of the Wall. Waters talks about his growing disdain for the sort of rock ‘n’ roll stadium audience whose participants just jumped on the bandwagon of popular trends or what was hot on the pop charts, following it to the venue. He says this is why he conceived the Wall. He truly wanted to separate the band from the audience and build a huge wall on stage that the band could play behind. He addresses a famous incident he seems a bit ashamed of in retrospect where he spit on a kid pushing his way toward the stage. “Afterwards I became really depressed and thought, ‘My God, what have I been reduced to?'” he says.

Besides insightful commentary from all band members, including the late keyboardist Rick Wright, the program features lots of fantastic professionally shot live footage of the band during some of only 29 shows they performed of the Wall. The few clips that appear are so well done, with multiple cameras, it makes you long for a full, live filmed performance. The band have often said that not enough of this quality footage exists to make a full, proper live concert video, however (Note: the image below is not representative of the picture quality on the DVD included in the Wall Immersion set, just on old still found from an earlier incarnation of the DVD, which has been remastered for this box set).

Though this is a DVD, many will be disappointed to learn there is no audio version of the album remastered into a 5.1 DVD surround mix. This feature was included in the only two other Immersion Pink Floyd reissues that have come out so far: the Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here. However, an interview with Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason revealed a 5.1 mix for the Wall had been planned and may see the light of day in a future reissue.

Instead, Pink Floyd fans will have to settle with visual material many may already be familiar with, albeit restored and improved over any of its earlier incarnations in both video and sound quality. There is also a restored video of the band’s famous single “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2” as well as a live performance of “the Happiest Days of Our Lives” that looks amazing with blue lens flares and multiple angles. The video comes to a stop just as the giant teacher puppet appears, however, fading out as Waters sings “We don’t need no education…” making for quite a cruel tease.

Finally, also on the disc is an extended interview with Scarfe from the Behind the Wall documentary and for Getty Images. It goes on for about 17 minutes and has some overlap with Behind the Wall, but features footage otherwise never released officially.

It is mostly him as a talking head with a few cutaway shots to his drawings. He talks about how his creative process with Waters and other animators, often in a long uncut monologue. There is also a nice moment when he stands next to a portfolio and explains some of his Wall illustrations, which were later turned into film sequences projected during the live show and then wound up in Parker’s film version.

The Demo CDs

Finally, the moment most of the hardcore fans of the Wall probably most anticipated: the more than two hours worth of demos, spread across two CDs included in this set, entitled “Work in Progress – Part 1 and 2 [respectively], 1979.” The sleeves of both discs feature “A word about the content of these ‘demo’ discs” written by Guthrie. He explains that Waters had produced “about 3 album’s worth of material,” only 14 minutes of which appear on these discs, he however notes. The rest are much fuller band demos trying to sketch out the running order of the album.

Considering the amount of demos and the redundancies here, I cannot harshly pass judgment on what is or is not included. I do not envy those tasked with weeding through the demos, sequencing them and putting them together into the interesting collages that fill the two discs included here, and they are interesting.

Disc 5 has a total runtime of 71:21. Programme 1, composed of the Waters demos, feels like a cruel teaser, as the tracks offer only a fraction of what were the first kernels of the Wall.  These 22 tracks, for the most part, fade away before they barely start. Some are as short as 19 seconds and definitely sound like they last longer, even though they may not be complete songs. They mostly feature Waters strumming an acoustic guitar with some effects thrown in here and there with snippets of him singing variations of lyrics that ultimately ended up on the Wall. There are some definite odd differences like the lyrics of “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2:” “I don’t need no education/I don’t need no rising water.” Hearing “Run Like Hell” as first conceived by Waters reveals a completely different idea until guitarist/vocalist David Gilmour had his input. The song sways in an almost country manner and had lyrics like, “You better run like hell if you wanna get away from here.” “What Shall We Do Now?” was first known as “Backs to the Wall” but included lyrics that did not change much at all, on the other hand.

These 22 tracks, for the most part, fade away before they barely start. Some are as short as 19 seconds and definitely sound like they last longer, even though they may not be complete songs. They mostly feature Waters strumming an acoustic guitar with some effects thrown in here and there with snippets of him singing variations of lyrics that ultimately ended up on the Wall. There are some definite odd differences like the lyrics of “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2:” “I don’t need no education/I don’t need no rising water.” Hearing “Run Like Hell” as first conceived by Waters reveals a completely different idea until guitarist/vocalist David Gilmour had his input. The song sways in an almost country manner and had lyrics like, “You better run like hell if you wanna get away from here.” “What Shall We Do Now?” was first known as “Backs to the Wall” but included lyrics that did not change much at all, on the other hand.

By the time Programme 2 starts, things grow even more interesting. This “programme” marks the start of the band demos, and they contain complete songs, including some that never wound up on the Wall or even changed completely into other songs on the album. One of these songs is “Teacher, Teacher,” a bright little tune that seems just a bit lighter than the rest of the music that wound up in the album. It’s an airy piece with an awkward shift into a chorus that seemed destined to the outtakes archive. Then there is the bluesy, meandering “Sexual Revolution” that runs out of words and momentum halfway through its five-minute runtime. Some of these demos rise above curious experiments, however. “In the Flesh” has a nice extended intro, featuring a quiet, acoustic guitar breakdown and distant moaning. Though the drums pop like gunshots, it loses some punch and fades away at the end.

The demos reveal the members of Pink Floyd as a band deeply involved in experimentation open to exploring ideas while refining their way to a masterpiece. The attention to detail throughout is impressive. Toward the end of the Disc 5, during Programme 3, a hint of the start of the album is offered, as the first six tracks of the album appear in sequential order, in rough demo form. The real concentrated power of the Wall now finally appears, though the recording quality is weak and some of the songs have been faded out and truncated. It ends with an incredible version of “Mother,” with added groans, screeches and sighs of synthesizers. It’s super-affected and weird with Gilmour going reverb crazy on bluesy electric guitar. Though not as moving as the spare album version most are familiar with, it carries a strange surreal— dare-I-say— druggy, psychedelic quality, as if a younger Pink Floyd were at work here.

At a runtime of 57:29, Disc 6 is shorter, but the demos are longer here, (though, once again, the music is not always complete). Programme 1 of this CD mixes both the Waters and the band demos. The first three tracks are Waters’ demos and reveals how much vision he had early in the process.  He uses many overdubs and even sings the bombastic drum part of “Bring the Boys Back Home.” The band demos begin with track four and an especially interesting, if over-the-top, version of “Hey You.” The dynamics are more intense than the final recording, as the band had yet to work out the song’s subtleties and add polish in the studio. “The Doctor,” later known as “Comfortably Numb,” opens very different from the final version, as Waters sings more literal lines before he toned the lyrics down for a more evocative quality. It again offers a great example of how fine-tuned the album came to be. There is a second version of “The Doctor (Comfortably Numb)” during Programme 2 of the disc where Gilmour sings all of the lyrics. You can tell the band was searching for something with this track, and these working versions, though fine in themselves, are testament to the detailed wringer the band put its creativity through. A name change to “Comfortably Numb” would make for a smart capper to the many tweaks the song later went through.

He uses many overdubs and even sings the bombastic drum part of “Bring the Boys Back Home.” The band demos begin with track four and an especially interesting, if over-the-top, version of “Hey You.” The dynamics are more intense than the final recording, as the band had yet to work out the song’s subtleties and add polish in the studio. “The Doctor,” later known as “Comfortably Numb,” opens very different from the final version, as Waters sings more literal lines before he toned the lyrics down for a more evocative quality. It again offers a great example of how fine-tuned the album came to be. There is a second version of “The Doctor (Comfortably Numb)” during Programme 2 of the disc where Gilmour sings all of the lyrics. You can tell the band was searching for something with this track, and these working versions, though fine in themselves, are testament to the detailed wringer the band put its creativity through. A name change to “Comfortably Numb” would make for a smart capper to the many tweaks the song later went through.

The songs on the second “Work in Progress” disc are also more distinctive. “Run Like Hell” features guitars that sound so crystalline they practically sparkle. The echo is so luscious at times it sounds as if they are playing the music under water. You can just hear Waters and Gilmour grooving along for the sake of indulging in this exaggerated sound effect. It fades away before it gets too indulgent, though, and it sill makes for a treat, nonetheless. Many of the demos on this disc have a sheen that sounds more produced than the previous demo disc. Sometimes it’s too a fault. “One of My Turns” goes off grooving on an organ down a terrible street as Waters’ singing falls embarrassingly out of synch.

Finally, the second demo disc wraps with Gilmour’s slight contributions. He sings “do-dos” mapping out the lyric structure of “Comfortably Numb” on a dreamily affected acoustic guitar, and then there is an electric, wah-wah instrumental version of “Run Like Hell.” The two tracks provide not only clear insight into how he participated in the songwriting versus Waters but also how important these slight but essential contributions were to a couple of album highlights.

Final thoughts

With Independent Ethos, I do not just limit myself to obscure titles, artists or films, though it often might seem so. There are many popular works out there that come from a creative, personal space, and this fancy box set thoroughly explores one of the most iconic progressive rock albums that ever did indeed come from such a space. Despite all the trinkets and extras that seem to pad this “immersion” experience of the Wall, the truly exciting aspect of this box lies within its music and its treatment. Even the visuals come after the music. There are seven discs included here, but it’s barely enough to contain all the interesting aspects of Pink Floyd’s 1979 double album. The music alone, but also the picture books, were enough to throw me back to a time when this album just came out. I may have been a kid in elementary school, but the presence of the album in popular music already made an impression in my mind.

Though I was too young to enjoy the original tour of the Wall in 1980-81, I do count myself among many that have seen Roger Waters’ recent live show of the full album (Waters’ ‘the Wall’ live cements theme with vivid production). Last month, Waters once gain came to the same venue in my area for another one of these shows, and this time I reviewed it for “County Grind,” one of the blogs on the “Broward/Palm Beach New Times” website. This time, they secured a pair of tickets for me, and I had a view from the floor. You can read that review and see lots of close-up pictures by jumping through the following photo taken of Waters at the show:

The tour continues as I post this long-in-the-works blog post (pardon the length), including stops at larger stadiums than this tour was ever first designed for. Visit Roger Waters’ website for the remaining tour dates. Finally, the Wall Immersion set is available at most stores. If you purchase it through Amazon via this link, you will be supporting this blog with a commission provided by Amazon at no extra charge to you.

*The Shine On box set was designed by Thorgerson.

The other day, I shared an interview compiled from a series of emails exchanged with the UK-based poet Rick Holland, who most recently worked on a collaborative album with rock’s most famous intellectual, Brian Eno (Eno collaborator/poet Rick Holland corresponds on craft – An Indie Ethos exclusive [Part 1 of 2]). Drums Between the Bells (Support the Independent Ethos, buy the limited edition on Amazon) saw release by Warp Records back in July. I had been exchanging emails with Holland since late June, as he considered several questions I had about his collaborative work with Eno.

The other day, I shared an interview compiled from a series of emails exchanged with the UK-based poet Rick Holland, who most recently worked on a collaborative album with rock’s most famous intellectual, Brian Eno (Eno collaborator/poet Rick Holland corresponds on craft – An Indie Ethos exclusive [Part 1 of 2]). Drums Between the Bells (Support the Independent Ethos, buy the limited edition on Amazon) saw release by Warp Records back in July. I had been exchanging emails with Holland since late June, as he considered several questions I had about his collaborative work with Eno.

He took his time, and I offered it to him. He wrote out my questions and journaled answers in hand-written notebooks before writing me back with thoughtful answers. But he also sent me back some spontaneous emails with thoughts on further questions. Though this certainly allowed for much editing of thoughts, I think it appropriately reflected the craft of what he and Eno did together. After all, Drums Between the Bells, with its electonic-based music and deliberately read poetry (sometimes presented in a haze of another layer of electronics), is anything but a jam record. The Eno/Holland collaboration is a thoughtful work, and grows with age and listening investment.

When I began my undergrad art studies in the early nineties, I took a mix of Eno’s instrumental music on a portable cassette player to art galleries and parks. Who better to offer musical accompaniment to art? His music can range from subtle drones to hyperkinectic layers of poly-rhythmic dissonance. It also defined a new genre of music in the mid-seventies that Eno himself coined: ambient. What better composer to offer a musical track to a poet who crafts artistic prose that can both observe the world on its existential face and cut into the fabric of perceptions? My favorite track on Drums, must be “Pour It Out,” adapted from Holland’s poem “New York” from his Story the Flowers book (It’s all there):

But then the album as a whole offers its own dynamic journey through a variety of prose and musicality (In the interview below, Holland notes the complete process of writing, recording and producing this album took eight years). Throughout our correspondence, Holland offered some dense insight into the process of crafting Drums Between the Bells, and also provided an illuminating look into the mind of a poet well-suited to work with someone as intellectual as Brian Eno. Before I continue with this interview, which you will find concluded below, I feel it’s important to contextualize the significance of a new, original, Eno-composed album featuring words.

Eno has been recording solo albums since 1973. He broke out of England’s post-prog scene of glitter and feathers glam rock, after leaving Roxy Music. All the while, he made a career of coming to terms with the role of words in music. Eno famously considers the function of words within songs as just another instrument rather than a literary narrative with a message, as the implications behind the latter throw in a huge monkey-wrench into the ideas of composition for him.

Eno has been recording solo albums since 1973. He broke out of England’s post-prog scene of glitter and feathers glam rock, after leaving Roxy Music. All the while, he made a career of coming to terms with the role of words in music. Eno famously considers the function of words within songs as just another instrument rather than a literary narrative with a message, as the implications behind the latter throw in a huge monkey-wrench into the ideas of composition for him.

Citing from Brian Eno: His Music and the Vertical Color of Sound, the Eno-centric website More Dark Than Shark, quoted Eno as having said, “[Lyrics] always impose something that is so unmysterious compared to the sound of the music [that] they debase the music for me, in most cases.” That was back in 1985. I thought surely his attitude towards lyrics had changed by the time he recorded his first solo vocal album in 25 years, 2005’s Another Day on Earth (Support the Independent Ethos, purchase on Amazon).  It seems it has. In an interview with Sound on Sound (a music magazine for the studio engineer) promoting that album, Eno said of his return to music with vocals: “The simple answer is that five or six years ago I noticed that I was starting to sing again and enjoying it. Also, since I stopped doing vocal albums and worked on the landscape side of music, certain technological developments have happened that give you the possibility to shape your voice, and that reawakened my interest.”

It seems it has. In an interview with Sound on Sound (a music magazine for the studio engineer) promoting that album, Eno said of his return to music with vocals: “The simple answer is that five or six years ago I noticed that I was starting to sing again and enjoying it. Also, since I stopped doing vocal albums and worked on the landscape side of music, certain technological developments have happened that give you the possibility to shape your voice, and that reawakened my interest.”

This technological idea of obscuring the voice of the singer was key for Eno, in that it seems to separate identifying the singer with the words he is singing. “One of the reasons I stopped making vocal records was because I was fed up with the identification that’s always made between the voice on the record and the composer, as if this person singing was some sort of extension of my personality,” he continued in the 2005 interview. “But I don’t care about my personality being the content of the thing. I always liked the idea of seeing what I was doing the way a playwright might think of a play or a novelist might think of a book.” So chalk up Eno’s growing distaste for lyrics to the influence of mostly “illiterate” music journalists and fans he must have encountered during his many years as a rocker.

To the ears of this writer, Eno’s attitude to lyrics produced some amazingly surreal and pure prose in his early years, but the later years of his lyrics never seemed to stand out as some of his more remarkable works, as it all must have worn thin on him by then.  Now here comes the 32-year-old Holland, invited by the 63-year-old Eno to provide him with some of the most refreshing words in many years for Eno to work with. The result, which suitably features an array of guest vocalists who have nothing to do with the rock world– as noted in the first part of this interview series– certainly has brought my attention back to words entangled in Eno’s music. In the end, Drums Between the Bells offers something even more interesting than Eno’s most recent work with a better known songwriter and long-time collaborator, David Byrne, for the pleasant, albeit predictable, 2008 album Everything That Happens Will Happen Today (Support the Independent Ethos, purchase on Amazon).

Now here comes the 32-year-old Holland, invited by the 63-year-old Eno to provide him with some of the most refreshing words in many years for Eno to work with. The result, which suitably features an array of guest vocalists who have nothing to do with the rock world– as noted in the first part of this interview series– certainly has brought my attention back to words entangled in Eno’s music. In the end, Drums Between the Bells offers something even more interesting than Eno’s most recent work with a better known songwriter and long-time collaborator, David Byrne, for the pleasant, albeit predictable, 2008 album Everything That Happens Will Happen Today (Support the Independent Ethos, purchase on Amazon).

With that context in place, on with the interview with Holland, who, in this part of the feature, offers his ruminations on the best place to listen to Drums Between the Bells, the music of words and even an evaluation Eno’s early explorations of lyric-writing on 1973′s Here Come the Warm Jets (Support Independent Ethos, purchase on Amazon) and 1974′s Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) (Support Independent Ethos, purchase on Amazon)…

Hans Morgenstern: Can I just say that I read this article (Clash Music’s Aug. 7 interview with Holland), and the fact that Brian says Drums Between the Bells is a good album to “wash up to” was funny to me because that was the first way I heard it (whilst taking a shower). So where’s the best place to hear the album in your opinion?

Rick Holland: In a state of stillness akin to lucid dreaming where surface concerns are replaced by free and contemplative activity that is not self-conscious. In the absence of this elusive brain state, washing up sounds a pretty strong contender. I have most enjoyed listening while driving on a long journey; though the best time for achieving this brain state seems to be in the middle of the night listening to incidental sounds mashing up – I like to use the sounds as triggers to imagine whatever comes into my mind. A flow is achievable in this state that is very much reduced when ‘recording’ art from imagination to medium. Getting near to that state is probably ‘the best place’ to listen to this album, where judging brain is dampened and imagining brain is electric, and as free to move as electric as long as the circuit is in place and not interrupted.

As I noted in an earlier post on Drums Between the Bells (Brian Eno reveals full streams of 3 tracks from new album), I was attracted to this Eno record because he seems to finally be dealing with lyrics on a deeper level than usual. Has he told you why he was interested in putting your words to music?

Strangely enough we have never had that conversation, we just got to work. I did learn through the process that ‘lyrics’ served a greater master: ‘sound’ in world Eno, but also that he was not closed to them as carriers of their own potential, but that he was overjoyed for the ‘meaning’ to become tied in with different axes of sound and atmosphere, and be loosely and ambiguously tied to the more conventional systems of language.

Is there anything on the album the could have been done differently? If so, how?

Is there anything on the album the could have been done differently? If so, how?

The whole album could have been done differently; it spanned eight years or so, and at any particular juncture in that time I would have had strong ideas about what could have been done differently. There were techniques available in the last three weeks of work that were not available in the first seven years, and early tracks with components that were lost forever in archival glitches and were rebuilt. There were times when I wanted only to feature the voice, and other times I wanted the voice obliterated into signals bearing no obvious resemblance to speech. At various points we would try versions of each of our visions, and make a piece that really and truly was not the end product of either of those visions. I would make the whole album differently if we started again tomorrow, and so would Brian. From ‘Drums Between The Bells’, all of the experiments have been successes in my eyes, but all of them have also suggested future alternatives. People who listen to the record will have strong ideas of what can be done differently too. That is one of the album’s great strengths; it moves in between territories, music, words, sound, that are familiar and then alien and many points in between. That aspect of it I wouldn’t change at all.

Do you have any rhythm or music in mind when your poems come out of you?

Cover for 'Story the Flowers,' Holland's first book featuring the poems that were part of 'Drums Between the Bells.'

The words themselves dictate the rhythm, set it running like a free drum part, but I would say I have an instinctive relationship to music and rhythm in my writing more than a trained one. To steal directly from something I heard Rakim say in a documentary the other night, ‘I was trying to rhyme like John Coltrane played the sax’. Fundamental rhythms and music have moved me since I can remember, and these are definitely built in to my writing without ever feeling the need to adhere strictly to traditional ‘poetic’ forms and meter.

From what source do you find most inspiration comes from when composing?

The world playing out in front of me. If pushed to identify a trigger, I would say pattern formation followed closely by sound. ‘Artificially’ speaking, music and especially live performance fills my gut with a kind of adrenalised need to express something.

Have you read reviews of the album? What do you think of the reception? Do you think music critics are “getting” it?

I went on a journey with the criticisms of the album. I ignored common wisdom that says ‘do not read reviews’ and actually ended up being encouraged to read them and respond in a ‘blog conversation’ with Brian (which itself headed off piste straight away). Like everything, some are good and some are bad, but of the critics who were able to put time and investment into listening and avoid the understandable traps of rushing out copy, I think the reception was fair. For a reviewer wanting to be transported without challenge, ‘Drums Between The Bells’ may seem an unnecessary challenge of disparate ideas and sounds. And it is completely reasonable to expect music to be a portal to elsewhere that doesn’t need to be ‘got’. If a reviewer came to the album with no expectations and a little time to think, they almost unanimously found things that resonated strongly in the experience. There are of course plenty of comments, good and bad, that are wide of a mark that I would recognize, and a few that have made me want to contact the writer and vent some spleen, but life is short.

I would say that our need as a society to quickly package anything is indicative of a wider approach to the world that has serious pitfalls, but I am not so self-important to think that someone ‘not getting’ this album is significantly important to the wider good of humanity. I wish people would stop harping on so much about ‘Art’, ‘Poet’, ‘genre’ and other blanding agents, but it is for each person to decide how he or she perceives what is really only a collection of sounds and relationships, like any music. Brian and I came up with some categories for songs when putting the running order together, they were ‘think’, ‘look’, ‘feel’ and ‘soul,’ I think, or similar with several crossovers.

I’m very curious of what you think of Eno’s early forays into lyrics, which he himself has called nonsense, but I feel have an unabashed surreal quality.

I scanned (thanks to Enoweb) through the lyrics for ‘Here Come the Warm Jets’ because I haven’t listened to that album, so I thought it would be a good appraisal of the ‘lyrics’ as standalone … the scanning happened quite fast until I hit ‘Dead Finks Don’t Talk.’ This was the first thing that caught me as more than words to be sung that had been transcribed. From what I know of Brian, the sounds will most likely have come before the actual words, but in this automation there is still subconscious coupling of sounds with emotions, and emotions with word choices, and word choices with streams of more ‘macro’ patterns of thought.

I scanned (thanks to Enoweb) through the lyrics for ‘Here Come the Warm Jets’ because I haven’t listened to that album, so I thought it would be a good appraisal of the ‘lyrics’ as standalone … the scanning happened quite fast until I hit ‘Dead Finks Don’t Talk.’ This was the first thing that caught me as more than words to be sung that had been transcribed. From what I know of Brian, the sounds will most likely have come before the actual words, but in this automation there is still subconscious coupling of sounds with emotions, and emotions with word choices, and word choices with streams of more ‘macro’ patterns of thought.

Rappers freestyle in 16 bar salvos. Through practising and writing more, the rhythms and internal variations within those rhythms develop so much so in the best rappers that they become second nature until they act as a conduit for whatever the consciousness wants to express. I think good lyrics are the same beast and are no less ‘poetry’ because of it; if anything they are more so, as they are perhaps more likely to avoid the pitfalls of over-analysis on the way out.

‘Dead Finks Don’t Talk’ on the page could be about any ‘authority’ figure in any walk of life who is more bluff than balls, and it also has interjections from less primary sources of input like modernist poetry (which may have taken that tendency to mix and match from a world of songs and televisions and technology anyway). ‘More fool me, bless my soul’ sounds like a blues phrase co-opted, especially repeated. The ‘perfect masters/thrive on disasters/look so harmless/til they find their way up here’ is pure 16 bar beat riffing when I read it on the page. So, in the interests of science, I listened to the song after reading the lyrics to see what happens to them in the song…

At which point I realised I have heard this song before! No matter, I wrote all the above before realising that. The ‘more fool me, bless my soul’ was unsurprisingly musical, though more Buddy Holly than I was expecting. The lyrics in this song are certainly not nonsense, though that doesn’t mean that they have been set out to work as words on a page (which, in this case, they certainly do. I enjoyed reading them).

I’ll try the same approach with the ‘Whale’ song [“Mother Whale Eyeless”] you mentioned, which I haven’t heard before.

This reads like an appraisal of life in a country even more at the mercy of its media and propagandas than the one we live in now. It reads as highly political and highly poetic. ‘Don’t ever trust those meters’, ‘there is a cloud containing the sea’, ‘parachutes caught on steeples’, these all sound like the product of automatic writing that has been introduced to and bedded into an environment; the environment has been made by constantly observing the world in an imaginative way (‘stirring the air’ I called this in my own early poems about escaping from the claustrophobic world around me). At its start it reminded me of the impression I got from ‘A Day in the Life’ when I listened to it as a kid. ‘Got up, got out of bed, dragged a comb across my head…. somebody spoke and I went into a dream’. It says the details of our politicised lives are as ridiculous as they are pervasive, and that we, as individuals, are in turn angered, powerless and gloriously alienated from those details. Our bonds in life are all constructs ultimately.

This reads like an appraisal of life in a country even more at the mercy of its media and propagandas than the one we live in now. It reads as highly political and highly poetic. ‘Don’t ever trust those meters’, ‘there is a cloud containing the sea’, ‘parachutes caught on steeples’, these all sound like the product of automatic writing that has been introduced to and bedded into an environment; the environment has been made by constantly observing the world in an imaginative way (‘stirring the air’ I called this in my own early poems about escaping from the claustrophobic world around me). At its start it reminded me of the impression I got from ‘A Day in the Life’ when I listened to it as a kid. ‘Got up, got out of bed, dragged a comb across my head…. somebody spoke and I went into a dream’. It says the details of our politicised lives are as ridiculous as they are pervasive, and that we, as individuals, are in turn angered, powerless and gloriously alienated from those details. Our bonds in life are all constructs ultimately.

Then I listened to the song…

“Mother Whale Eyeless” is a fascinating song, unmistakably Brian in places, I would have to say. That brilliant simple guitar riff after about two minutes, the change and shift with the female chorus vocal. But anyway, the words, the words. The thing is, the morning papers, tea and other details are already shaken to their core by the way they are sung and spiral away from the details I picked up reading the lyrics straight away. It says a lot about the ‘lyrics’ debates that go on, the words on a page are a wholly different animal from the words performed and adorned.

If I had just listened to that song straight away, I would not have listened closely to most of the words, I must admit (though certainly would have picked up more with repeated listens). I would have started in the kitchen, then moved on to the guitar-feeling and then moved into the otherworld of the clipped female chorus and settled on the statement, ‘In another country, with another name/ Maybe things are different, maybe they’re the same’ as a carte blanche for anything that doesn’t make sense to float on unrepentant for being nonsense, because it might make sense under different circumstances, and the next evocation of something more ‘graspable’ may be just around the corner. I’ve always made these kinds of allowances listening to music, ever since I can remember. There is something perfectly sensible about that approach to writing words and to listening to them too. The eyeless whale chuckles at the world’s myths. Nonsense?

If I had to choose between the two experiences, in this case, I would choose reading the words, which is a surprising outcome. ‘Mother Whale Eyeless’ is a poem on the page for me (maybe because I approached it like this first) and the song is an event with some exciting moments but holding less meaning overall for me, at this moment. Perhaps this tells us that anything is ultimately what we make it. Perhaps it also tells us that Brian was writing poetry in spite of himself, and perhaps it also tells us that his instinctively curious approach to the world manifests itself clearly in the groups of words he chooses to fit together, which certainly isn’t a surprising outcome. I mentioned (skilled) rappers earlier so used to their molten bedrock that what they can sprinkle on top of it is almost instinctive. This doesn’t make their output less important or interesting.

If I had to choose between the two experiences, in this case, I would choose reading the words, which is a surprising outcome. ‘Mother Whale Eyeless’ is a poem on the page for me (maybe because I approached it like this first) and the song is an event with some exciting moments but holding less meaning overall for me, at this moment. Perhaps this tells us that anything is ultimately what we make it. Perhaps it also tells us that Brian was writing poetry in spite of himself, and perhaps it also tells us that his instinctively curious approach to the world manifests itself clearly in the groups of words he chooses to fit together, which certainly isn’t a surprising outcome. I mentioned (skilled) rappers earlier so used to their molten bedrock that what they can sprinkle on top of it is almost instinctive. This doesn’t make their output less important or interesting.

Brian understands his vocabularies and their potentials so well that the more cumbersome ‘word’ part I would imagine does not excite him as much as other things: ‘sound’, ‘voice’, ‘space’, ‘colour’ being a few. Doubly so when you consider that he has been making music for several decades and is always keen to explore new possibilities.

* * *

Many thanks to Rick for taking the time to entertain these questions and offering such an enlightening look into the experience that culminated in one of the richest albums 2011 has had to offer! Not to mention indulging me with his honest view of some early iconic Eno glam rock songs that he had never heard to start with.

Eno collaborator/poet Rick Holland corresponds on craft – An Indie Ethos exclusive (Part 1 of 2)

September 5, 2011

A couple of months ago, I sent poet Rick Holland a link to my post sharing my excitement about the results of his participation with Brian Eno, Drums Between the Bells (Support the Independent Ethos, buy the limited edition on Amazon). He wrote back graciously expressing his appreciation for my “kind words.” He also said he would pass my email on to Warp Records, as I had expressed an interest in an advance listen of the album.* Though that did not happen, I stayed in touch with Holland for a profile piece on “Independent Ethos,” the results of which are now ready for posting in this multi-part interview series.

A couple of months ago, I sent poet Rick Holland a link to my post sharing my excitement about the results of his participation with Brian Eno, Drums Between the Bells (Support the Independent Ethos, buy the limited edition on Amazon). He wrote back graciously expressing his appreciation for my “kind words.” He also said he would pass my email on to Warp Records, as I had expressed an interest in an advance listen of the album.* Though that did not happen, I stayed in touch with Holland for a profile piece on “Independent Ethos,” the results of which are now ready for posting in this multi-part interview series.

Holland identifies himself as “Rick” as the sender in email correspondence. It’s a nice detail that offers an appropriate gateway to understanding the young man (he’s 32) who wrote the lyrics of “The Real:”

you really seem to see the real

the exact and actual reality

of the real in things you seem to see

And that is only a taste of the mind-bending words Holland explores in “the Real.” The song opens with the crystal clean voice of 22-year-old Elisha Mudly. Like many of the participants on Drums Between the Bells, the “vocalists” are not rock stars (though some of the reading was done by Eno).  Mudly is a drama/psychology student and dancer who had worked for Eno “around the studio, sorting stuff etc.,” she told me via Facebook. “Brian and Rick were working on this project and they just asked if I’d like to read something quickly. So, had some tea, read some poetry and then we said goodbye,” she explained (as the interview with Holland continues below, he emphasizes the serendipitous appearance of Mudly in the studio, as a happy coincidence that resulted in the smooth recording of that track).

Mudly is a drama/psychology student and dancer who had worked for Eno “around the studio, sorting stuff etc.,” she told me via Facebook. “Brian and Rick were working on this project and they just asked if I’d like to read something quickly. So, had some tea, read some poetry and then we said goodbye,” she explained (as the interview with Holland continues below, he emphasizes the serendipitous appearance of Mudly in the studio, as a happy coincidence that resulted in the smooth recording of that track).

On “the Real,” Mudly reads with quiet, ethereal purpose as ambient drones swell and recede, like the wash of waves on the sea shore, beneath her voice. Taking the words to a whole other brilliant level, the bed of drones continue as the words are repeated. This time, however, Eno slows down Mudly’s voice a notch and decorates it with a shimmering vocoder effect, repeating the words exactly as before… but not. The implications of the words and Eno’s use of them reveals a brilliant creative connection between the two artists.

Holland’s awareness of the subjective quality of perceptions seemed to reveal an intellect that would indeed find a kinship with the mind of a thinking musician like Eno. In an  interview with Michael Engelbrecht on the Germany-based blog, Manafonistas, Holland described a true collaborative relationship with Eno, when he described an instance when he requested a certain “sound” from the music: “I do offer musical ideas and also extremely vague and over-reaching requests: ‘Can you make this part sound more like primordial sludge, Brian?’ That kind of thing. Of course, his answers tend to be, ‘Yes, yes, I can.’”

interview with Michael Engelbrecht on the Germany-based blog, Manafonistas, Holland described a true collaborative relationship with Eno, when he described an instance when he requested a certain “sound” from the music: “I do offer musical ideas and also extremely vague and over-reaching requests: ‘Can you make this part sound more like primordial sludge, Brian?’ That kind of thing. Of course, his answers tend to be, ‘Yes, yes, I can.’”

Holland’s own direction to Eno sounds just like the sort of language Eno would understand well, as abstract as it might sound. Eno is the guy who devised the Oblique Strategies card set with painter Peter Schmidt in the early seventies with similar sorts of directions, if sometimes even more obtuse (Read all about Oblique Strategies).

I wanted to know more about their album, Drums Between the Bells, which has easily grown into one of my favorite Eno albums in many years, and I do consider it among the best albums I have heard this year. Though Holland is certainly in the shadows next to a man often called the pioneer of ambient music and known as the producer of U2’s and Coldplay’s highest regarded albums, Holland’s contributions of words to Drums Between the Bells is key to elevating this work to a higher level. Just as earlier Eno collaborations, like Fourth World Vol. 1 – Possible Musics, would have never been the same without Jon Hassell’s trumpet or Ambient 2: The Plateaux of Mirror without Harold Budd’s piano, Drums would have never floated to its otherworldly quality without the words of Holland (an instrumental-only second disc in the deluxe version of this album provides the bare evidence of this).

I wanted to ask him about working with Eno and how the collaboration worked. The problem was I live in Miami and Holland splits up his time in London and Dorset, England, so long distance would be rough on either of us struggling writers. I had done email interviews in the past (Read one I did with Melt Banana here), so I was wary (Melt Banana, being Japanese noise surrealists provided perfect answers in their own quirky way, but I was really hoping for some deep insight from Holland on working with Eno). When he told me he would write out my questions to respond via notebook and then write them again in an email, I knew I would be in for some interesting, thoughtful responses. So allow me to begin the interview with that: Why would Holland go through such trouble to respond to my questions…

I wanted to ask him about working with Eno and how the collaboration worked. The problem was I live in Miami and Holland splits up his time in London and Dorset, England, so long distance would be rough on either of us struggling writers. I had done email interviews in the past (Read one I did with Melt Banana here), so I was wary (Melt Banana, being Japanese noise surrealists provided perfect answers in their own quirky way, but I was really hoping for some deep insight from Holland on working with Eno). When he told me he would write out my questions to respond via notebook and then write them again in an email, I knew I would be in for some interesting, thoughtful responses. So allow me to begin the interview with that: Why would Holland go through such trouble to respond to my questions…

After I explained my own experience with the effect of writing longhand and then re-writing in a computer (the process alone seems akin to writing as many as three drafts before coming up with a finalized piece), Holland wrote back the following:

Definitely of the school of rewriting … I have come full cycle back to notebooks, having started with pieces of paper.

I think writing by hand, poetry or lyric-wise and probably longer pieces or articles too, is the best approach in the early stages. The closest I have come to the same effect electronically is by emailing myself repeatedly. Write ‘poem’, email it to self, redraft on first reading, email it to self, fiddle, email it to self, go to bed, read it and email to self. Continue process to finish or abandonment. This approach allows the same kind of overall approach that doesn’t cripple the piece in self-analysis but does allow small and important changes to feed into the work without too much head-scratching or too many changes at once.

The temptation to edit while you write is too strong on a word processor of any kind, I find. Now, if I have a eureka moment (very rare at a computer anyway) I write it in my notebook if I have it– I usually carry it around everywhere– or on a piece of paper, or increasingly as a ‘draft’ on my mobile phone. The trick is to remember to check the ‘drafts’ or look again at the notebook or transfer the scribble to notebook or computer. If I transfer it early to a computer and do the ’email thing’ then it is likely to get finished. If I don’t, then it may re-emerge as something quite different in the future.

This is what I started my blog [rickholland’s posterous] for as well actually (see you have got me started now) : a live notebook, to air ideas and return to them. Because they are in a public place, it probably means my vanity will make me check back over them more than I would do in a paper notebook. This is no bad thing, as I tweak them online, and consumer behaviour (I think) doesn’t really pay much attention to old blog entries anyway, so the effect really is only that of an evolving notebook. I have conditioned myself to ‘post’ things on there in their imperfect state, which is against our instincts, and sometimes they remain just fine as imperfects… another ‘condition’ is to only post things that I am genuinely working on at the time or am finding interesting and learning about.

I thought that email was a candid response that offered an intimate glimpse into how this young poet works and how seriously he takes the significance of words.