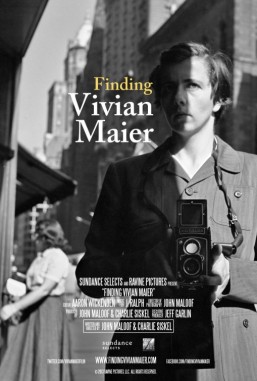

Though it celebrates a creative person yearning to express herself above monetary gain and fame, there’s something disconcerting about the new documentary Finding Vivian Maier. The problem is apparent from the beginning, when co-director John Maloof inserts himself in the story to define success for the woman photographer who never achieved recognition while alive. It starts with a box of photographs he found during one of his treasure hunts at a low-rent auction house. He would uncover hundreds of prints, negatives and even roles of undeveloped film. He puts some of the images up on the Internet, and he’s surprised with the interest. Cha-ching!

Though it celebrates a creative person yearning to express herself above monetary gain and fame, there’s something disconcerting about the new documentary Finding Vivian Maier. The problem is apparent from the beginning, when co-director John Maloof inserts himself in the story to define success for the woman photographer who never achieved recognition while alive. It starts with a box of photographs he found during one of his treasure hunts at a low-rent auction house. He would uncover hundreds of prints, negatives and even roles of undeveloped film. He puts some of the images up on the Internet, and he’s surprised with the interest. Cha-ching!

But, no! He does it for the art. He seeks appraisal from professional photographers, who tell him, at best Maier was a prolific but mediocre artist. No matter, according to the comments, shares, etc. on a Flickr post featuring Maier’s photos, the Internet likes the work. He has an exhibit at the Chicago Cultural Center, located in the city where Maier took most of her street photos in the 1950s and 1960s. The people come. There is interest. He signs prints in her absence and fills in orders from the hungry public who see something in the photographs of Maier worth paying fine art prices into the thousands of dollars. He also has the work archived and tries to find out who the woman was, and here is where the story gets interesting.

Maloof who also shot the film but co-directed with Charlie Siskel finds family members who hired her as a nanny. The children have grown up, and do they have some stories to tell. At first, these anecdotes start intriguingly with the interview subjects invited to sum up their experience with Maier using one word. “Eccentric” is used more than once. It would turn out taking the children out to the park allowed Maier to take her street photographs. It also gave the kids learning experiences that left profound impressions on their psyches. One woman recalls one outing when Maier took her to a sheep farm where she saw death in all its horror. Though it proved a downright grim experience for the child, it made for some great photographs for Maier, who seemed to have a kinship with Diane Arbus for the work’s grit but minus its surrealism.

These stories gradually reveal both a sad soul with a penchant for hoarding and a woman looking to express herself in defiance of the glossy notion of the idealism of the ‘50s and ‘60s. She even prefers a matte finish on her prints.  Maloof uncovers recordings she made, self-portraits and even receipts to tell her story, beyond the talking heads. It paints a rather full picture, and unlike the way he presents the work (he does have an interest in making it profitable, after all), it’s an intriguing wart-filled portrait that adds depth to her work, which often features imperfect people caught in unguarded moments thanks to the Rolleiflex camera she used to shoot with, which was positioned around the waist instead of at eye-level.

Maloof uncovers recordings she made, self-portraits and even receipts to tell her story, beyond the talking heads. It paints a rather full picture, and unlike the way he presents the work (he does have an interest in making it profitable, after all), it’s an intriguing wart-filled portrait that adds depth to her work, which often features imperfect people caught in unguarded moments thanks to the Rolleiflex camera she used to shoot with, which was positioned around the waist instead of at eye-level.

She’s an intriguing, flawed human being who found an outlet to express herself while remaining reclusive and ultimately dying alone. But, actually the film feels like the worst kind of self-promotion above art. It’s the businessman taking full advantage of art without the artist benefiting. It’s decorated in this feel-good movie. Oh, what a wonderful thing Maloof has done for a woman with no legacy or inheritors. There’s something rather disingenuous in the motivation behind this film. What really matters is promoting the art as something harmless and nice.  Cue the sprightly, pretty music building from fluttering flutes to jaunty strings to connote success and look at the crowds that attend gallery openings (look, there’s Tim Roth!). It all feels so self-important it gets rather sickening. There is a hint that maybe Maier had wanted to have these photos published somewhere, but most of all she produces with a human urgency to communicate, even if it’s after her death.

Cue the sprightly, pretty music building from fluttering flutes to jaunty strings to connote success and look at the crowds that attend gallery openings (look, there’s Tim Roth!). It all feels so self-important it gets rather sickening. There is a hint that maybe Maier had wanted to have these photos published somewhere, but most of all she produces with a human urgency to communicate, even if it’s after her death.

So the question most interestingly posed by this film is whether the work of Maier is art after all. Maloof defines it as an interest by the public (and there’s a lot for him to benefit from with that perspective). But, thankfully, he also defines it in the stories about Maier and who this woman was, a person who could not seem to put down her Rolleiflex camera. Like all good art, it depends on how you look at it. I just wish I only had to watch half of the film, instead of the commercial component and all the self-promotion disguised as feel-good Success(!) that really does nothing honest to redeem this sad woman ignored in life beyond two adults she cared for as children, who decided to put her up in her twilight years in an apartment … far away from them.

Finding Vivian Maier runs 83 minutes and is not rated (human fallibility abounds). In the South Florida area, it opens at O Cinema Miami Shores on Thursday, May 8, the Miami Beach Cinematheque and Living Room Cinema 4 in Boca Raton, on Friday, May 9. IFC Films provided a DVD screener for the purposes of this review. The film is also playing nationwide and on demand; visit the movie’s website for screening dates (this is a hotlink).